If you live with post‑traumatic stress, you’ve heard the refrain: connection heals. Here’s the grounded version—use a sturdy, platonic friendship as part of recovery. When it’s deliberate, a steady, non‑romantic bond can soften hyperarousal, chip away at avoidance, and rebuild trust. Those are not small things; they’re the levers symptoms ride on.

Women are nearly twice as likely as men to develop PTSD, and about 6–8% of people experience it across a lifetime. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs put the lifetime risk at roughly 6% in a 2021 overview. You are not alone. And this approach is underused.

Table of Contents

Why platonic friendship to heal PTSD works

- Social buffering of stress: Being with a trusted person dampens the body’s stress response. A classic lab study found that supportive presence, paired with oxytocin, reduced cortisol spikes and anxiety during a stress test (Heinrichs et al., 2003). That’s co‑regulation—two nervous systems settling together. My view: we underestimate how often a calm voice at the right moment does more than any app.

- One of the strongest predictors: Meta‑analyses show that lack of social support after trauma is among the strongest predictors of persistent PTSD (Brewin et al., 2000; Ozer et al., 2003). On the flip side, strong social ties are linked with better survival across 148 studies and 308,849 people—about a 50% boost (Holt‑Lunstad et al., 2010). The health stakes of connection are not soft science. The Guardian reported on this “loneliness penalty” in 2023; it’s real, and it’s costly.

- Nervous system logic: Polyvagal theory proposes that safe eye contact, warm prosody, and steady presence cue the “social engagement system,” turning down fight/flight (Porges, 2011). In plain terms, your body learns it’s safe in the presence of another safe body. I think of this as teaching the brain it’s world is bigger than the trauma.

How to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD: a step‑by‑step plan

1) Choose the right friend

- Look for reliability, emotional steadiness, and respect for boundaries—not a fixer, not a savior.

- Share your goal: to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD through small, repeatable practices, not crisis venting alone. Put that out early; it sets the frame. One opinion here: consistency beats intensity every time.

2) Co‑create consent and boundaries

- Agree on time windows, topics, touch preferences, and “pause” signals.

- Script it: “If I dissociate, please say my name and ask me to name five things I see.”

- Clear limits protect both people from burnout and shame. Boundaries are scaffolding, not walls.

3) Build a co‑regulation routine

- Two times per week, a 20‑minute walk, side‑by‑side (less intense than face‑to‑face).

- Five minutes of paced breathing together (inhale 4, exhale 6).

- A warm drink check‑in ritual.

Social support reliably reduces physiological arousal; even brief, regular contact can lower baseline stress (Hostinar et al., 2014). These tiny anchors help you use platonic friendship to heal PTSD on ordinary days—not just hard ones. If it feels “too simple,” that’s a feature.

4) Tackle gentle micro‑exposures together

- With your therapist’s guidance, list avoided‑but‑important activities (e.g., grocery store at off‑hours).

- Rate fear 0–10. Start at 2–3 with your friend as a calm buddy.

- Track distress (SUDS) and repeat until the number drops by half, then level up.

This mirrors in‑vivo work from Prolonged Exposure therapy, where graded approach reduces avoidance and threat appraisal (Foa et al., 2007). It’s a practical way to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD without turning your friend into a therapist. My bias: progress measured in half‑steps lasts longer.

5) Behavioral activation buddy

- Schedule three mood‑boosting, values‑based activities per week (sunlight walk, plant care, short yoga, making a playlist).

- Text “done” upon completion; reply with a simple emoji or “proud of you.”

Physical activity and activation reduce PTSD and depressive symptoms, which commonly co‑occur (Rosenbaum et al., 2015). Accountability helps you use platonic friendship to heal PTSD through consistent action. It’s easier to move when someone’s waiting.

6) Communication tools that protect the bond

- Use “color codes”: green = chat; yellow = need listening only; red = short grounding and reschedule.

- Try reflective statements: “What I hear is…” before advice.

Mutuality keeps it sustainable and makes it easier to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD over months, not days. One rule of thumb: leave each contact a touch more regulated then you started.

7) Crisis and safety plan

- Share a one‑page plan: triggers, helpful steps, what not to do, emergency contacts.

- If you’re in the U.S. and at immediate risk, call 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) or 911.

A clear plan means you can confidently use platonic friendship to heal PTSD without confusion in tough moments. Preparedness is not pessimism—it’s care.

Measuring progress together

- Pick one outcome measure (weekly PCL‑5 short form or a simple 0–10 symptom tracker). Look for 5–10 point drops over weeks.

- Track sleep, avoidance days, and how quickly you return to baseline after triggers.

- Celebrate “boring wins”: fewer canceled plans, shorter spirals. Data helps you use platonic friendship to heal PTSD in a way that’s encouraging and concrete. I’d argue boring wins build recovery more than breakthroughs.

Pitfalls when using platonic friendship to heal PTSD

- Turning your friend into a therapist: Keep processing trauma content for therapy; use the friendship for regulation, exposure companionship, and life‑building.

- Over‑reliance on one person: Aim for a small team—friend, therapist, peer group. Diversify the net.

- Boundary drift: Revisit limits monthly. A 10‑minute “how is this working?” protects both of you. Better to adjust early then repair later.

Conversation scripts to make it easier

- The ask: “I’m working on recovery and want to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD. Would you be open to a 20‑minute walk twice a week and occasional buddy trips to places I avoid? No therapy—just company and check‑ins.”

- The boundary: “I care about you and can do yellow today, not red. Can we ground for five minutes and plan a longer talk tomorrow?”

- The win share: “I went to the store at 10 a.m. Fear went from 6 to 3. Thanks for the texts.”

Scripts are not cages—they’re ramps into hard conversations.

Why this is especially powerful for women

Women have higher PTSD risk and face more interpersonal traumas. Support that is safe, consistent, and non‑romantic can repair trust and agency without the complications of dating dynamics. That’s exactly why many clinicians encourage clients to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD alongside evidence‑based therapy. In my experience, this form of support restores choice—which trauma often steals first.

Closing thought

Trauma isolates; healing reconnects. When you deliberately use platonic friendship to heal PTSD—through co‑regulation, micro‑exposures, and mutual boundaries—you give your nervous system hundreds of proof points that the world can be safe again. Start tiny, track progress, and let consistency do the heavy lifting. It’s not flashy. It works.

Summary

A steady, non‑romantic bond can calm the stress system, reduce avoidance, and restore trust. Combine weekly co‑regulation rituals, therapist‑guided micro‑exposures, and clear boundaries to use platonic friendship to heal PTSD. Measure small wins and protect mutuality so the bond stays strong over time.

Call to Action

Ask one trusted friend today to try a 2‑week “healing buddy” experiment—two walks and one easy exposure.

References

- Heinrichs, M., Baumgartner, T., Kirschbaum, C., & Ehlert, U. (2003). Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. https://journals.lww.com/psychosomaticmedicine/Abstract/2003/11000/Social_Support_and_Oxytocin_Interact_to_Suppress.4.aspx

- Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for PTSD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-02829-010

- Ozer, E. J., et al. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-07509-005

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine. https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3108032/

- Hostinar, C. E., Sullivan, R. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2014). Psychobiological mechanisms underlying social buffering of the HPA axis. Social Neuroscience. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4039080/

- Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-05986-000

- Rosenbaum, S., et al. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of PTSD: A systematic review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jts.21906

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). PTSD: National Center for PTSD—How common is PTSD in adults? https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

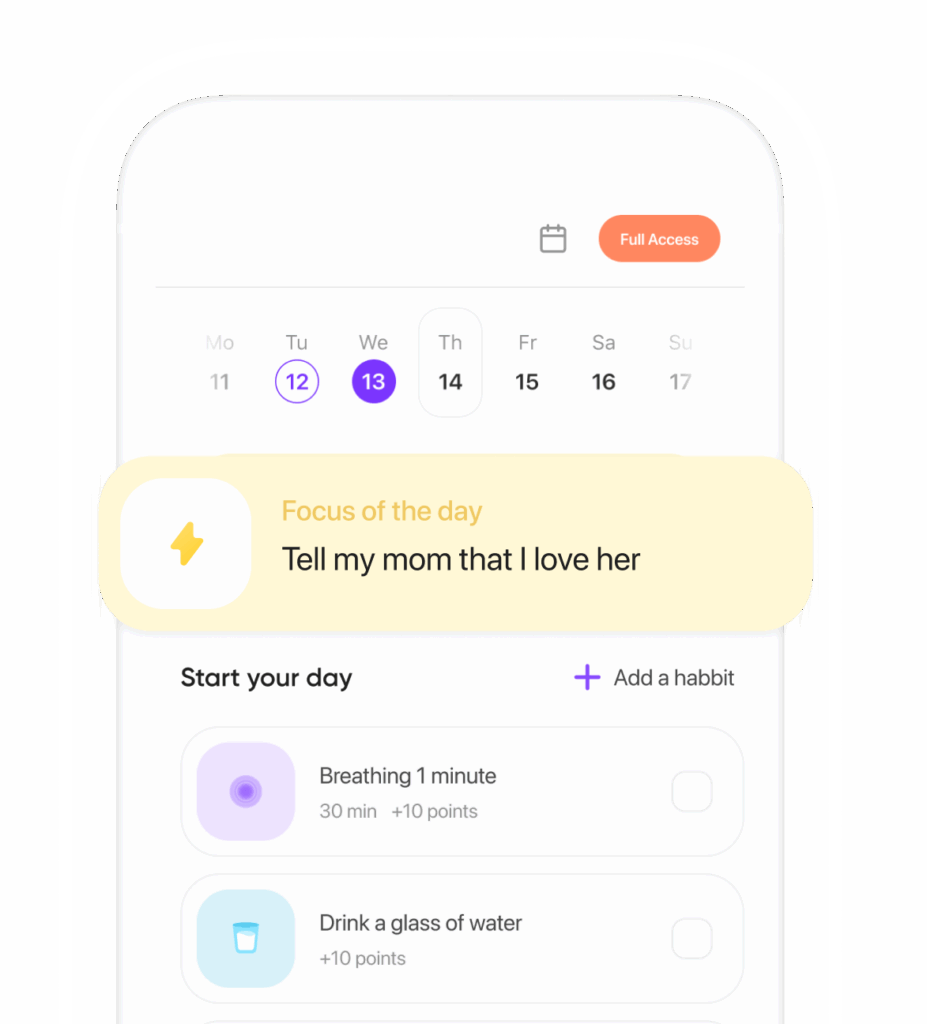

Ready to transform your life? Install now ↴

Join 1.5M+ people using AI-powered app for better mental health, habits, and happiness. 90% of users report positive changes in 2 weeks.